A couple of weeks ago I was asked by TechUK to speak about British innovation at the Embedded World exhibition and conference in Nuremberg. The UK is the fourth largest exhibitor — after the hosts Germany, the US and Taiwan — and this was an opportunity, along with colleagues from Intel and Imagination Technologies, to look at how the UK excels.

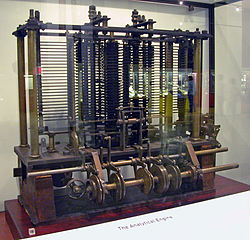

Great Britain has a strong history in computers, starting with Charles Babbage and his Analytical Engine, the world’s first general purpose computer. Alongside Babbage was the world’s first programmer, Ada Lovelace. The UK also saw the world’s first programmable electronic digital computer in Colossus during World War II, with the theoretical foundations of computing being laid by Alan Turing in Cambridge. In the late 1940’s there were three computers in the world, EDSAC in Cambridge, “Baby” in Manchester and the Mark I at Harvard, while in the 1951 the UK provided the first business computer, the Lyon’s Electronic Office, or LEO I.

Today, UK computer engineering is still a power house. Take apart any modern smartphone, and you’ll find a processor designed by ARM (Cambridge), graphics from Imagination Technologies (Kings Langley), Bluetooth & audio from CSR (Cambridge) and high speed data from Icera (now part of Nvidia, but based in Bristol). Even where you do find a US company like Broadcom with a chip in there, it was largely designed in their Bristol and Cambridge R&D centres.

In a competitive global environment, this leadership needs all the help it can get. Whilst a supportive business environment is the most important factor, the state also has a vitally important role to play. I have written before about the importance of the education system — not just at University, but at school — when children are deciding on their life interests. But another key factor is encouragement for transfer of ideas from University to industry. Germany has led the way with billions invested annually through its Fraunhofer Institute. The UK equivalent is Innovate UK (formerly known as the Technology Strategy Board), and it is a positive step to see the funding of this organization increase at a time when UK state spending has been cutting back hard. It is also positive to see the cross-party support. Its latest initiative setting up Catapult Centres is the result of a review commissioned by a Labour minister (Peter Mandelson), but implemented by a department headed by a Liberal Democrat (Vince Cable) in a Conservative-led government.

Embecosm has benefited from Innovate UK support. A Collaborative Research Program with Bristol University enabled us to develop the Machine Guided Energy Efficient Compilation System (MAGEEC), while a feasibility study grant allowed us to take Superoptimization from the research world into a commercially practical technology. In both cases, the work required was too risky to justify the entire investment by a company the size of Embecosm. Government help allowed us to carry out the work; the partial funding effectively reduces the risk to a level we can bear. It allows us to progress far faster, keeping a world-leading edge in our field. The work is high risk, otherwise state aid could not possibly be justified, but we have been fortunate that in both cases business success has followed. The first commercial use of superoptimization will start in April this year, with the first MAGEEC development beginning in July. As a result Embecosm has continued to grow, and the UK sees its pay back already through increased employee payroll taxes and corporation tax.

We have a long way to go before we match Germany’s success in transferring ideas from university research to commercial innovation. But the success of Innovate UK is a good sign and something to be very proud of.

This blog post is based on a talk given at Embedded World on 25 February 2015.